Phil Smith

Phil Smith is

an academic, writer and performer, who lives in South Devon, UK. For twenty

years he worked predominantly as a playwright in experimental, physical,

community and music theatres, during which time over one hundred of his plays

received professional productions. In 1997 his work took a sharp turn towards

working in non-theatre sites and this led to his interest in walking as both an

art in itself and as a means to making art and performance and everyday

political interventions in public spaces.

I have the pleasure to interview

Phil Smith again, this time advancing on from his theory and practice of Mythogeography – the art of ‘walking sideways’ – as an opportunity to learn about Counter Tourism, the subject of

Phil’s new project that includes micro-movies, online presence, and two new

publications: a pocketbook and a handbook for everyday tourists.

MM Which are the basic differences between Mythogeography’s

walks and the ones for Counter Tourism?

PS They are inspired by the same

ideas – those that come from the ‘drift’ or dérive – but where Mythogeography’s

walks (or at least their intentions) are unbounded, Counter Tourism takes the

boundings and prescriptions of heritage tourism as its object. Where Counter

Tourism’s visits step to the side or go off at tangents, they do so in order to

later loop back to the discourse of heritage tourism, in order to destabilize

or re-frame or vivify that discourse.

MM If we don’t feel nostalgia is that a problem? How does Counter

Tourism work in a country which we don’t know anything about?

PS In a way, such a visit, knowing

nothing, is already Counter Touristic. For heritage sites are very often

presented on the basis of invisible, unspoken but mutually understood

narratives. For example, in English country houses the lives of the uniformed

staff are often remembered and re-presented, but the non-uniformed staff (labourers, gardeners) are not. The

recognition of uniformed servants is regarded as a democratic innovation, but

it contains its own discrimination. So, actually preserving one’s lack of

knowledge or feeling might be a good tactic – you will very quickly begin to

feel the meaning-making machines get to work on you and that sensation might

illuminate the nature of the site and the nature of ideological production in

it.

MM Considering the attendance of British people to the trips of

Counter Tourism, what do you propose for a different culture, in other words is

there a pattern to follow or you’d change the strategy in another country?

PS When as a member of Wrights

& Sites I was part of publishing ‘An Exeter Mis-Guide’ we assumed that the

book would be mostly used in the city it as written about, yet it has been used

in many different countries – France, USA, India, Australia, and so on – as a

tool for exploration. Rather than me trying to anticipate how Counter Tourism

might be adapted for different countries I would rather leave that to people to

discover in their own improvised visits. At one point I write “if the guards

are armed” – there are no armed guards at UK heritage sites, so I am signaling

my awareness that conditions for visits will vary from country to country and

region to region.

MM Your research panel members come from a wide range of

working backgrounds. What’s your experience working with both professional artists

and also people with a background not related to arts and architecture?

PS Well, the whole basis of

Mythogeography is the idea of multiplicity so it was a joy to have so many

insights and perspectives. What the panel members brought were insights and

attitudes that disrupted many of my assumptions. Sometimes they de-composed

what I was thinking and doing, at other times their ideas and mine were

synthesized or fell into mutual orbits. It worked differently with different

people, but almost always adding to the multiplicity.

MM Why do you include popular songs and some informal

disguises, like hats? Is it a kind of postdramatic theatre?

PS There

is an inspiration for Counter Tourism in postdramatic theatre – yes,

definitely. The performance walks from which Counter Tourism developed might be

characterized in the way that that Hans-Thies Lehmann characterizes the

postdramatic: ‘disintegration,

dismantling and deconstruction’ , ‘de-hierarchization of theatrical means’ ,

and an ‘experience of simultaneity’

sited on a plane of synchronicity and myth: ‘not a story read from...

beginning to end, but a thing held full in-view the whole time... a landscape’.

Songs and disguises are for using sparingly – there is a danger that Counter

Touristic visits can flip over into showing off and exhibitionism. But in one

of the films - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gM7FZkd1Qaw

– I do sing, but I think I’m probably trying

everybody’s patience with this moment of self-indulgence! So hats and songs

maybe, but very sparingly!

MM Does everybody participate in the performances or maybe you

found reluctant ones among professionals?

PS When a visit is explicitly a

performance – like a mis-guided tour – then almost everyone will be prepared,

if asked, to take some active role or part – modeling ghosts or holding a rope

for me to ‘dangle’ from. I never set out to make people feel uncomfortable or

self-conscious, I always aim to make people feel comfortable and secure and

then challenge them to step a little way out of their comfort zone for the

purposes of the collective event. Using the Counter Tourism tactics people can

choose how performance-like or how discreet they want to be.

MM I was surprised to see that in GeoQuest video old people are

participating, also kids and adults. Is there any different approach for the

eldest?

PS Well, these were older people in

‘sheltered housing’ so the visit of the GeoQuest there had to be to them in

their homes rather than taking them to the site – so we took rocks and sand to

them rather than them visiting the cliffs and beaches. But no, apart from being

sensitive to our impact – the arrival of three men in strange costumes could be

disturbing for very elderly people if too noisy and boisterous – we treated

older people in the same way and with the same intentions as everyone else.

MM You say there are variations and re assemblages of what tourists

see based on their own experiences of life. Is it valid to manipulate them to

find the multiplicity of points of view?

PS I hope that Counter Tourism is

an offer rather than a manipulation. It requires the tourist to make a leap

that only they can make – one can offer the different viewpoints, but if a

visitor wants to stick to a homogenized narrative of the site then they will be

able to ‘pull the shutters down’.

MM In GeoQuest video, people are making sound with stones,

while the leader is playing a song related to geology, also in another scene,

people are using pink glasses. Is it part of the exorcism of familiar forms of

heritage?

PS Yes, I think “exorcism” is a very

good word to use – heritage (in this case a geological one) is often seen as a

view through “rosy coloured spectacles” (a nostalgic’ overly sunny view of the

past that confirms our own prejudices) and using the glasses forefronts and

challenges that tendency and then seeks to bend it to a new kind of impact. The

fundamental tactical-principle of counter-tourism is to exorcize or hollow-out

existing ways of visiting sites and then re-animate those ways in exorbitant

and excessive ways (either as spectral versions or highly coloured, comic or

emotional versions of themselves).

MM On the other hand you show the importance of signs on the

monuments’ walls - what’s the purpose of it, wouldn’t it reinforce the idea of

heritage?

PS I try to encourage people to

‘over-interpret’ the signs – rather than as simple narratives of the heritage we

can (half-seriously) read them as esoteric crypto-messages or discover double

meanings or you tell ourselves tales about how they unintentionally reveal the

secrets of the site.

MM Is it allowed to take pictures, if they are a static

representation of reality, not in the spirit of Counter Tourism?

PS O yes, even without a stills

camera or a video camera we see through those lenses and frames all the time –

just as many urban nineteenth century people might have seen the landscape as

if framed like a painting. So I suggest that we use those internal frames

knowingly – and photography can help – as well as being a means to disseminate

counter-touristic ironies and opportunities to others.

MM Based on the film of ‘Mythogeography’ at the Royal William

Victualling Yard, are mythogeography’s walks exclusively for students?

PS Not at all! I wanted to make a

film of this walk and I wanted to take my students on the walk as part of their

course – so I was ‘killing two birds with one stone’ – my walks are almost

always open to the general public and I have no idea who will turn up – often

my subject matter is adult but my means are playful, so children can often get

involved in those means – for example, in my recent ‘Spaces’ walk in Weymouth I

referenced the murders of a local serial killer and dragged around a bath (he

drowned his victims) – the children loved the way that the water in the bath

bounced around as I dragged it over the cobblestones (something I had drawn

everyone’s attention to as a useful means – the break up and reforming of the

site’s reflection - to re-interpreting the site).

MM In the overall context of Counter-Tourism, what was the

significance of your “water walk?”

PS Water Walk was a mis-guided tour

around an area of industrial heritage and former quayside in Exeter during

which we tried out some innovative ideas for a tour that came to have a bearing

on the devising of Counter Tourism – myself and the other guide began by

explaining that we were going to relinquish most of the roles of guides, we

told the audience all the history we were not going to tell them about on the

tour, we enacted all the pointing we would not be doing and we took off our

guides’ jackets – we then led the tour mostly in silence enacting various

secular rituals using water (crucial to the former industrial processes of

tanning, cloth manufacture, driving the water mills, and so on) – we ‘exorcised’

the tour and then resurrected its tactics in excessive ways. The responses of

participants were qualitatively different from other tours – not only did they

describe the multiple meanings of the sites appearing, but they became

self-consciously aware of how they were constructing a multiplicitous

heritage-consciousness while in the act of actually constructing it in their

own minds - this quality I came to attribute to this tour’s accessing of

‘chorastic’ qualities in the site - a space somewhere between being and

becoming, temporarily resistant to obligations of exchange and commerce, a

temporary evasion of identities and hierarchy, a potential space of

transformation, a transitory space that a particular kind of performance might

be able to provoke and sustain for a while. From this walk I took the idea of

the double movement (exorcism and excess) to which Counter Tourism subjects the

ordinary tactics of a tourist visit, the idea that the guide should step back

and let the participants be the driving force, and that the driving aim should

be access to the ‘chora’ of a site rather than the performance intervention in

it.

MM Is it helpful for your objectives to see the landscape

indirectly, for example through the many reflections on the water, or through

lenses, or to imagine the landscape through the sky?

PS Yes – frames and mirrors – I am

always using them and advocate them – they allow us to become aware of the

internalized frames, mirrors and representations that we use and make.

MM In Counter Tourism, can the human body have a direct

approach to Nature? I was just imagining myself laying on the grass, listening

to the sounds of Nature and in this way recreate the landscape….

PS Why not? Yes, sometimes there is

a moment to drop all the clever tactics and go for a direct sensual immersion –

but without any romantic illusions – there will be all the same ideological

framings at play even in this sensual act as in, say, an intellectual inquiry.

MM This question was inspired by thinking of the movie directed

by Andrei Tarkovsky, “Stalker” ; I suppose you find some relations between

Stalker and Counter Tourism?

PS To some extent, yes, because

‘Stalker’ is about a kind of pilgrimage which is partly ordeal – and both those

qualities can be introduced into the touristic visit with subversive or

disruptive effects. And, of course, pilgrimage and tourism have always been

close. I like to use anachronisms knowingly – to disrupt ideas of ‘progress’

and ‘modernity’.

MM What do you suggest for those tourists in the shopping malls

who are missing the “counter tourism” or even the conventional tourism?

PS I would say – do the counter

tourism in the malls. One of my tactics

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGAQTJAKSAA is to walk a mall

or supermarket as a zombie, treating the mall as the museum of a

post-apocalyptic society. In the Handbook I move on to discuss how all spaces

are heritage spaces – but some have a gate and a ticket office and some do not.

MM Where is Counter Tourism going?

PS I hope that it will be seized

upon as a pleasure by as many everyday tourists as possible – firstly as a

means for enjoyment, but one that will change the nature of heritage from a

looking backwards (whether serious and analytical or nostalgic and

chauvinistic) to what others have called ‘anticipatory history’ – a use of the

past for making the best futures.

MM Thank you so much Phil!

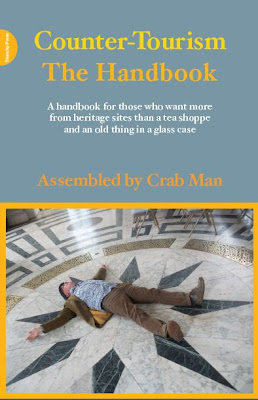

Above, three shots from the video Mythogeography at the Royal William Victualling Yard