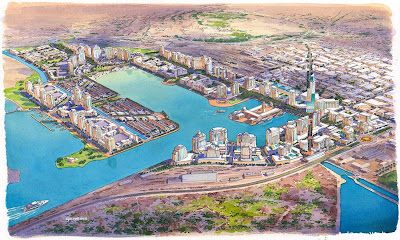

Proposed urban center on the Tunis waterfront by Peter Calthorpe, recipient of the 2006 J.C. Nichols Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development. Image: Calthorpe Associates. From http://www.architectureweek.com

In 1983, the British born architect, Peter Calthorpe gave up on San Francisco, where he was not successful at organizing neighborhood communities and moved to a boat house in Sausalito, a beautiful town on the San Francisco Bay. This 400 houseboats community of South 40 Dock is a very dense place. There, all residents know each other, including their pets, they pass each other on foot daily. It works as a community because, in Calthorpe’s words, it is walkable.

Based on this insight, Calthorpe became one of the leader proponents of New Urbanism, also called Neotraditionalism, along with Andrés Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and others. He is the author of Sustainable Communities, The Next American Metropolis, and most recently, The Regional City: Planning for the End of Sprawl (co-authored with William Fulton).

In 1985 he introduced the concept of walkability in “Redefining Cities,” an article in the Whole Earth Review, an American counterculture magazine that focused on technology, community building and the environment. Since then, new urbanism has become the dominant force in city planning, promoting high density, mixed use, walkability, mass transit, eclectic design and regionalism. It drew one of its main ideas from the houseboat community.

In his 1985 article, Calthorpe made a surprising statement: “The city is the most environmentally benign form of human settlement. Each city dweller consumes less land, less energy, less water, and produces less pollution than his counterpart in settlements of lower densities.”

Years after, in his interview, hosted by Scott London, 2002, Calthorpe stated (excerpts):

London: Most metropolitan areas seem to be moving in the opposite direction. For example, in Seattle the population grew by 36 percent between 1970 and 1990 while the developed land area grew by 90 percent. Cleveland’s population actually declined during that same period, but the city continued to spread outward.

Calthorpe: Yes, it’s because we’re building lower density suburban subdivisions at the periphery of regions. We’re not going back in and repairing and recycling older neighborhoods in inner-city areas, or even older suburban areas. It’s a disposable-society strategy to building cities — basically you use them then throw them away and move on to some virgin land. It’s a pioneer ethic. There’s no question that it’s in the blood of America. But at some point we have to recognize that we’re no longer pioneers on a frontier.

London: Will be able to turn things around?

Calthorpe: Democracies tend to be self-correcting, and I think we’re in a self-correcting mode now. We see the problems. The first and most profound sign of it is the anti-growth movement. People are saying "I don’t want any more development."

London: You’ve pointed out that we should be narrowing our streets and roads, not widening them.

Calthorpe: What is a street? It’s not just a utility for the car. It’s everybody’s most immediate neighborhood. At least that’s what it used to be — a place to walk, a place to bike, a place for kids to play, a place to park cars, a place for trees, and therefore a place for birds. To think of the street as just a utility for cars is so absurd. And yet that is exactly what is happening because we have segmented design so that the traffic engineer designs the streets and the civil engineer designs the utilities and the architect designs the buildings. Nobody is thinking about the whole composition. Narrower streets win in every way. They make cars go slower, which means that the neighborhood is safer for kids and more enjoyable for pedestrians.

Calthorpe´s theory is followed by others, and urban designers have a new point of view about urban overpopulation and density that is opposite to the traditional one. After all, they explain that it is not so bad the concentration of people in the cities.

Stewart Brand, one of the world´s most influential and controversial environmentalists, co-founder of The Long Now Foundation and the Global Business Network, also living on a houseboat in San Francisco Bay, exposes the reasons in his article ¨How slums can save the planet¨, published in Prospect. Issue 167. January 27th, 2010. I am showing here some of them.

¨The reversal of opinion about fast-growing cities, previously considered bad news, began with The Challenge of Slums, a 2003 UN-Habitat report. The book’s optimism derived from its groundbreaking fieldwork: 37 case studies in slums worldwide. Instead of just compiling numbers and filtering them through theory, researchers hung out in the slums and talked to people. They came back with an unexpected observation: “Cities are so much more successful in promoting new forms of income generation, and it is so much cheaper to provide services in urban areas, that some experts have actually suggested that the only realistic poverty reduction strategy is to get as many people as possible to move to the city.”….

¨The magic of squatter cities is that they are improved steadily and gradually by their residents. To a planner’s eye, these cities look chaotic. I trained as a biologist and to my eye, they look organic. Squatter cities are also unexpectedly green. They have maximum density—1m people per square mile in some areas of Mumbai—and have minimum energy and material use. People get around by foot, bicycle, rickshaw, or the universal shared taxi.

Not everything is efficient in the slums, though. In the Brazilian favelas where electricity is stolen and therefore free, people leave their lights on all day. But in most slums recycling is literally a way of life. The Dharavi slum in Mumbai has 400 recycling units and 30,000 ragpickers. Six thousand tons of rubbish are sorted every day. In 2007, the Economist reported that in Vietnam and Mozambique, “Waves of gleaners sift the sweepings of Hanoi’s streets, just as Mozambiquan children pick over the rubbish of Maputo’s main tip. Every city in Asia and Latin America has an industry based on gathering up old cardboard boxes.” There’s even a book on the subject: The World’s Scavengers (2007) by Martin Medina. Lagos, Nigeria, widely considered the world’s most chaotic city, has an environment day on the last Saturday of every month. From 7am to 10am nobody drives, and the city tidies itself up¨……

¨The Last Forest (2007), a book by Mark London and Brian Kelly on the crisis in the Amazon rainforest, suggests that the nationally subsidized city of Manaus in northern Brazil “answers the question” of how to stop deforestation: give people decent jobs. Then they can afford houses, and gain security. One hundred thousand people who would otherwise be deforesting the jungle around Manaus are now prospering in town making such things as mobile phones and televisions.

The point is clear: environmentalists have yet to seize the opportunity offered by urbanization. Two major campaigns should be mounted: one to protect the newly-emptied countryside, the other to green the hell out of the growing cities¨.

REFERENCES

This post was made adapted from and based on:

Stewart Brand. “ How slums can save the planet” in Prospect. Issue 167. January 27th, 2010

Interview to Peter Calthorpe, hosted by Scott London. Published in the Fall 2002 issue of the architecture journal CriT. (This interview was adapted from the radio series Insight & Outlook)

No comments:

Post a Comment